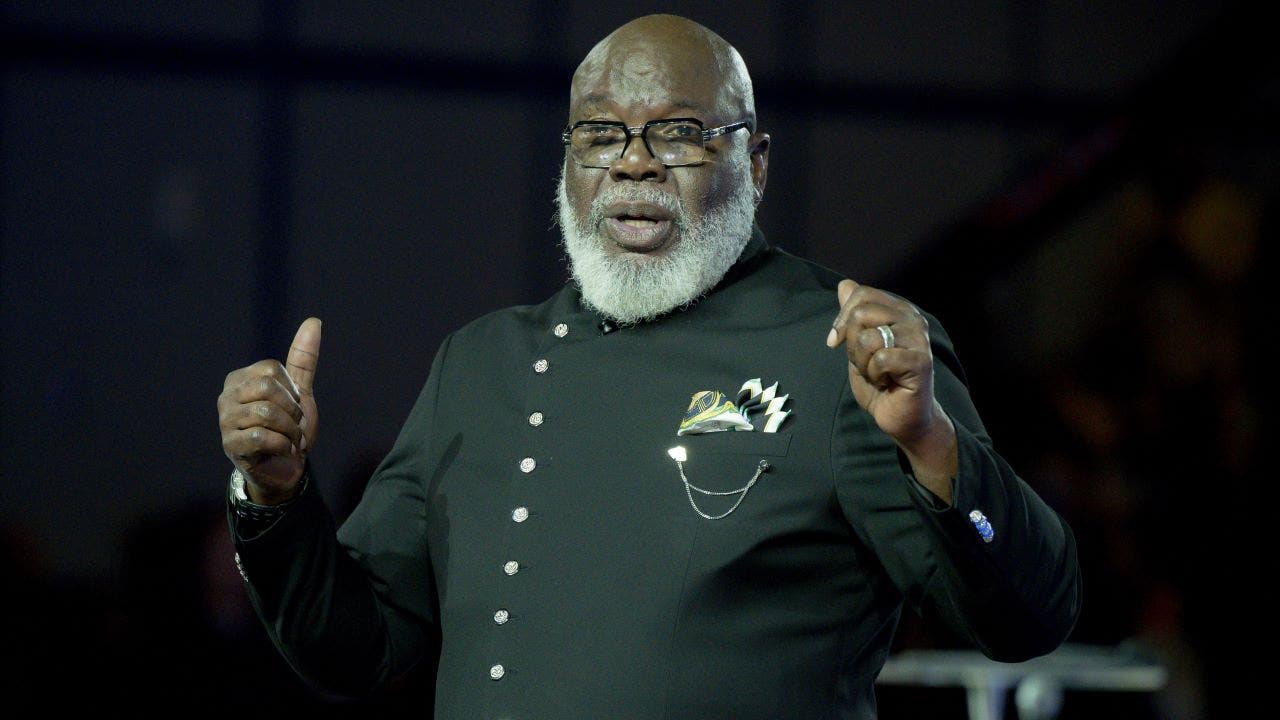

In one conservative Wisconsin county, the sheriff appeared onstage at a Donald Trump campaign rally last week to brag about his efforts to ban ballot drop boxes.

“I have something very important I think you’re going to want to hear,” Sheriff Dale Schmidt told Trump. “In Dodge County, in this 2024 election, there are zero drop boxes for the election.”

That wasn’t accurate – but the crowd cheered, and Trump offered the sheriff a double thumbs-up.

Around the crucial battleground state of Wisconsin, ballot drop boxes are a political flashpoint, with a tool that made absentee voting easier and safer during the pandemic-era 2020 election now highly contested.

In the state’s two biggest and most liberal cities, drop boxes are plentiful, with voters able to drop off their ballots at more than a dozen locations in each city, from fire departments to libraries. In some other cities and towns, however, local leaders have rejected them.

The controversy comes as the legal landscape on the issue has shifted dramatically from election to election: Drop boxes were legal in Wisconsin in 2020, then mostly banned in 2022, and now are legal once again after liberals took control of the state Supreme Court.

According to data from the Wisconsin Elections Commission, there are at least 78 drop boxes being used in the state during the general election, although that is likely an undercount because local clerks are not required to report drop box locations to the state commission. Still, that’s far lower than the 528 drop boxes that the commission was aware of in 2020.

Whether to use them is largely left up to the more than 1,800 local officials who administer the state’s elections. The cities of Milwaukee and Madison will each be using 14 drop boxes, and other cities and towns across the state are using one or several.

Nick Ramos, the executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a voting rights group that has pushed for more drop boxes, said he was discouraged by the number of municipalities that had decided not to use drop boxes this election.

“We’re watching almost what feels like a coordinated campaign by some bad actors here in this state to apply pressure and bully clerks into not putting drop boxes out,” Ramos said. “It’s become a lightning rod.”

Polls have shown Wisconsin to be one of the closest swing states in this year’s presidential race – four years after President Joe Biden won the state by less than 1 percentage point.

The most dramatic fight over drop boxes this election season has been in Wausau, a city of about 40,000 people that’s a blue dot in a red county.

Last month, Wausau Mayor Doug Diny, a Republican, put on a white hard hat and high-visibility gloves and wheeled the city’s ballot drop box into his office. The drop box was locked and not in use at the time.

Diny documented his action by sending photos of himself moving the box to the city clerk and other local officials. But under a state Supreme Court decision this summer, decisions about drop boxes were left up to local clerks, not mayors. His actions went viral.

Now the Wausau drop box is back in place in front of City Hall, where it is secured to the ground, locked and emptied daily by local officials. Meanwhile, the city clerk referred the controversy to the county prosecutor, and the state Department of Justice is investigating Diny’s actions.

In an interview with CNN, Diny said he hadn’t done anything illegal and had moved the drop box because it was unsecured at the time.

“For all I know, you know, somebody could have grabbed it, thrown it in the river,” he said. “Now we would have a real crime on our hands.”

Asked whether he regretted the move, Diny responded, “there’s a saying that dogs don’t bark at parked cars. I’ve had to get attention here from time to time to upset the status quo.”

But voting rights advocates condemned his actions.

“No one person gets to take the law into their own hands and interfere with someone else’s right to vote,” said Jeff Mandell, the general counsel of Law Forward, a public interest law firm in the state that has worked on voting rights cases. “If he finds that drop box to be problematic, of course he is welcome, like anyone else, to voice his opinion. … What he can’t do is unilaterally interfere with other peoples’ rights to lawfully vote.”

At a raucous City Council meeting last week, supporters and detractors of Diny packed the council chambers. One voter blasted what they called the “the deep state right at work in little Wausau,” while another said the controversy made her “embarrassed” for her city. Diny proposed spending $3,000 on additional security for the drop box, but the council did not vote on his proposal.

Outside City Hall, police officers were on hand to ensure tensions didn’t boil over between protesters supporting the drop box – who showed up wearing their own hard hats – and those who opposed it.

“We are fed up with politicians using conspiracy theories, no matter which party you support,” said Nancy Stenzel, a Wausau resident, to boos from opponents. “Drop boxes are safe, they are reliable and secure.”

For years, ballot drop boxes were legal in Wisconsin with little controversy or attention, and in 2020, they became a key tactic for municipalities to encourage safe voting during the coronavirus pandemic.

In advance of the election that year, Republican leaders in the state acknowledged that drop boxes were secure. In a letter to the Madison clerk in September 2020 objecting to a separate ballot collection process, A lawyer representing Robin Vos, the speaker of the State Assembly, and Scott Fitzgerald, then the state Senate majority leader, included drop boxes as ballot delivery methods they supported, citing state rules.

“We wholeheartedly support voters’ use of any of these convenient, secure and expressly authorized absentee-ballot-return methods,” the letter said.

But after Trump’s loss, Republican leaders changed their tune. When the Wisconsin Supreme Court rejected Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 results in December of that year, three of the court’s conservative members suggested that drop boxes were not actually legal under state law.

And in his January 6, 2021, speech just before the Capitol riot, Trump specifically singled out Wisconsin’s drop box policies, falsely claiming that drop boxes in the state “disappeared” for days.

A conservative group filed a lawsuit to ban drop boxes in Wisconsin, and the state Supreme Court’s conservative majority sided with them in 2022, banning drop boxes except ones inside clerks’ offices. That ruling – which was applauded by GOP leaders like Vos – was in place for the election that year.

Then in 2023, liberal Judge Janet Protasiewicz won a seat on the state’s high court, shifting the 4-3 conservative majority to a 4-3 liberal one. A few weeks before Protasiewicz joined the court, the Democratic group Priorities USA filed a lawsuit challenging the 2022 drop box decision.

In July, the court overturned the 2022 ruling, with the liberal justices arguing it was incorrectly decided. The new court majority left it up to Wisconsin’s more than 1,800 municipal clerks to decide whether to use drop boxes during the upcoming general election.

Now, Wisconsin voters are facing a patchwork of local policies on drop boxes. Some cities that used drop boxes in 2020, including Kenosha, the state’s fourth-largest, have decided not to use them this election.

Elsewhere in the state, cities are using the same drop box locations they used four years ago. In Milwaukee, most drop boxes are in front of libraries, and in Madison, the state capital and a Democratic stronghold, officials decided to locate almost all of their drop boxes in front of fire stations.

Dylan Brogan, a spokesperson for the Madison city government, said the city’s drop boxes were under constant video surveillance, and that the fire stations were well-suited to host the boxes because they were staffed 24/7 and spread out around the city.

“This is just a very convenient, easy option that voters can really trust,” he said.

Wausau isn’t the only place in Wisconsin where conservative elected officials have tried to take drop boxes out of commission this year.

In Dodge County, a county of about 90,000 people that voted heavily for Trump in 2020, Schmidt, the elected sheriff, urged local clerks not to use drop boxes.

“I strongly encourage you to avoid using a drop box,” he wrote in an August email to three clerks in his county obtained by the website WisPolitics, saying that doing so would “degrade trust in our system.”

When Schmidt told the clerk in one town that her municipality would be the only one in the county to use a drop box, she wrote back 15 minutes later to say that she had decided to close the box, WisPolitics reported.

Earlier this month, Schmidt took a victory lap at a Trump rally in Juneau, Wisconsin, where the former president offered him the double thumbs-up. Schmidt told CNN that Trump personally called him up to the stage.

“If we have an area of the law which is constantly being subverted, we’re going to find ways to put roadblocks in the way of individuals that are going to break the law,” Schmidt said.

When pressed on the lack of evidence that drop boxes were violating any law, Schmidt said, “there is the appearance that that it is occurring, and we are making sure that it is not going to happen.”

Eric Hovde, the Republican nominee for US Senate in Wisconsin, has also promoted doubts about drop boxes.

“We’ve got to make sure that there’s somebody standing by that drop box literally 24 hours a day, you know, for, you know, 45 days to make sure that you don’t have people just jumping, jamming fake ballots,” Hovde told supporters in July, The Washington Post reported.

Some conservative activists say they are planning efforts to do just that kind of surveillance. The conservative group True the Vote, which has pushed conspiracy theories about voting fraud, sent staff across Wisconsin in recent weeks to collect “exact drop box locations” in advance of setting up video livestreams of the boxes, the group’s director, Catherine Engelbrecht, wrote in an email to supporters earlier this month.

“True the Vote is providing camera gear, hotspots, and streaming support,” Engelbrecht wrote. “We’ve also written to states, counties, cities, and other municipalities, requesting ballot dropbox video footage, from the time the dropboxes are opened until close on Election Day. Unlike what happened in 2020, we are now very well prepared on this front.”

Another activist with the group described True the Vote’s efforts as creating “a dropbox surveillance reality show” in a Truth Social post that was later deleted, WIRED reported.

Mandell, of Law Forward, said that plans like those raised concerns about voter intimidation.

“Of course people have the right to observe the drop off of absentee ballots,” he said, “but there’s a very thin line between that observation and intimidation.”

Read the full article here